Life is tough. Of course, it has never been less tough, what with our modern medicine and ‘delete boredom’ machines we carry with ourselves everywhere. But it is still tough.

And so is university. How do we consider it a good, productive way to treat our young people? A hot bed of energy, emotions and proximity, with some sort of relatively abstract learning thrown in (yes, it varies by course, I know) and a swathe of useless hours followed by late nights and missed deadlines. It might build character, but surely it’s a bit of a high price to pay for that.

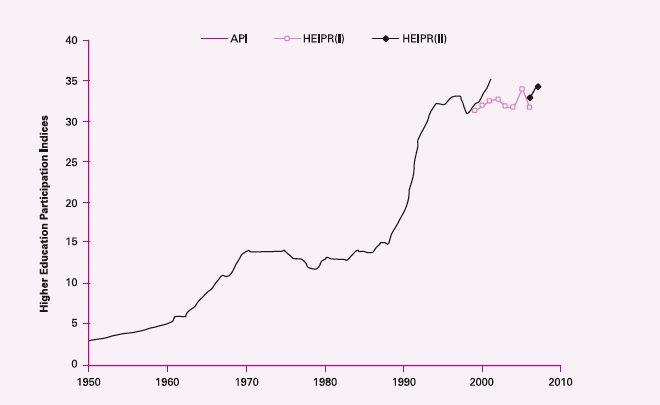

The problem isn’t that it is a chaotic teenage nightmare – though it is – the problem is that this is a very expensive and almost counter-intuitive way to enable chaotic teenage nightmares. I don’t think we really recognise just how recent a phenomenon mass university attendance is, and it is worth reminding ourselves that it was only in the 1990s that it exceeded 15%.[1][2]

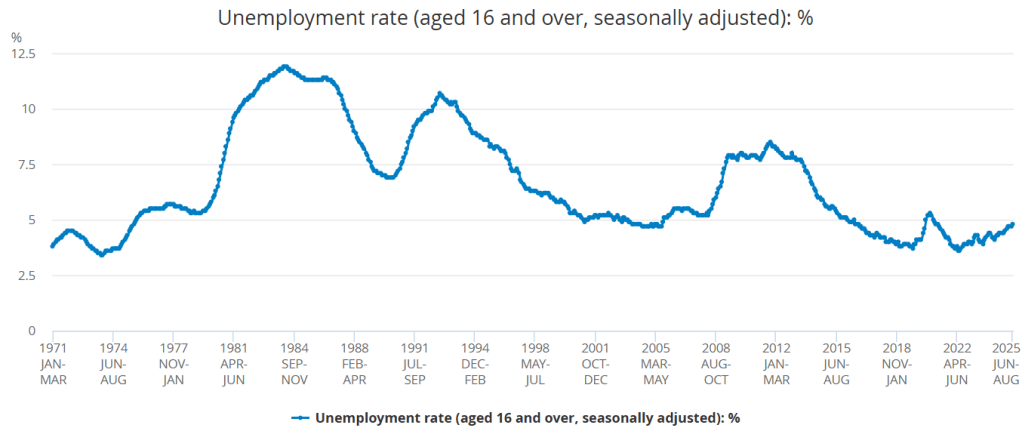

So, what has the main consequence of the growth in universities been, then? Well, it is hard to say. There has been remarkably little change in the sort of employment people are in, with the trends that do exist mostly consisting of a continuation in the decline of the manufacturing sector, something that was ongoing well before university attendance increased,[3] and something that is not good. Unemployment is slightly lower, but it was lower still in the 1970s when very few people had degrees.[4]

Such few changes in the economy have no doubt contributed to some of the highest rates of overqualification in the developed world, around 3 in 10, and I must confess that it is amusing to see the Higher Education Policy Institute (HEPI) get a little defensive at the suggestion that there could be too many graduates in Britain.[5] Instead, they hasten to add, “overqualification in the UK is likely driven, not so much by an oversupply of graduates as by a failure to create enough middle-skill jobs and robust vocational pathways outside universities.”

And, well, yes. We are in agreement, HEPI. But do these “middle-skill jobs” and “robust vocational pathways” really need universities? I don’t think they believe that they do, but they must admit, then, that we have focused too much on education and too little on figuring out what to do with all these educated people.

To be completely clear, I am not trying to downplay the role of universities in the UK economy, or suggesting that they shouldn’t exist, or even saying that going to one is a bad personal choice – it’s probably quite a good one.

No, what I am trying to say is that how we set up our country is a choice. How we educate our young people is a choice. Societally, do we really need, or want, to skim away so much talent from “real life” and established communities, leaving them disintegrating as our student cities struggle to cope with the outsized demand? People will be people – when surrounded by like-minded folk, they will have fun and make good discussion, regardless of where that is. There is nothing inherently special about university, intellectually or otherwise, and I think those who attend could do with appreciating this.

[1] Granted, a lot of the 1990s boom was from the conversion of the Polytechnics to universities, but the main consequence of that seems to have been a loss of the highly technical and niche (read as important) courses they offered, such as transport planning, something I intended to study but one that has been gradually culled until its final remaining provider, Aston University, packed up shop in 2024.

[2] Robertson, S. 2010. Globalising UK Higher Education. LLAKES. 8(2), pp. 191-203. [Online]. [Accessed 23 October 2025]. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/248935907_Globalising_UK_Higher_Education

[3] Office for National Statistics. 2019. Long term trends in UK employment: 1861 to 2018. [Online]. [Accessed 23 October 2025]. Available from: https://www.ons.gov.uk/economy/nationalaccounts/uksectoraccounts/compendium/economicreview/april2019/longtermtrendsinukemployment1861to2018

[4] Office for National Statistics. 2025. Unemployment rate (aged 16 and over, seasonally adjusted). [Online]. [Accessed 23 October 2025]. Available from: https://www.ons.gov.uk/employmentandlabourmarket/peoplenotinwork/unemployment/timeseries/mgsx/lms

[5] Henseki, G. and Green, F. 2024. Is England really the world champion in overqualification? Higher Education Policy Institute. [Online]. [Accessed 23 October 2025]. Available from: https://www.hepi.ac.uk/2024/12/23/is-england-really-the-world-champion-in-overqualification/

Leave a comment