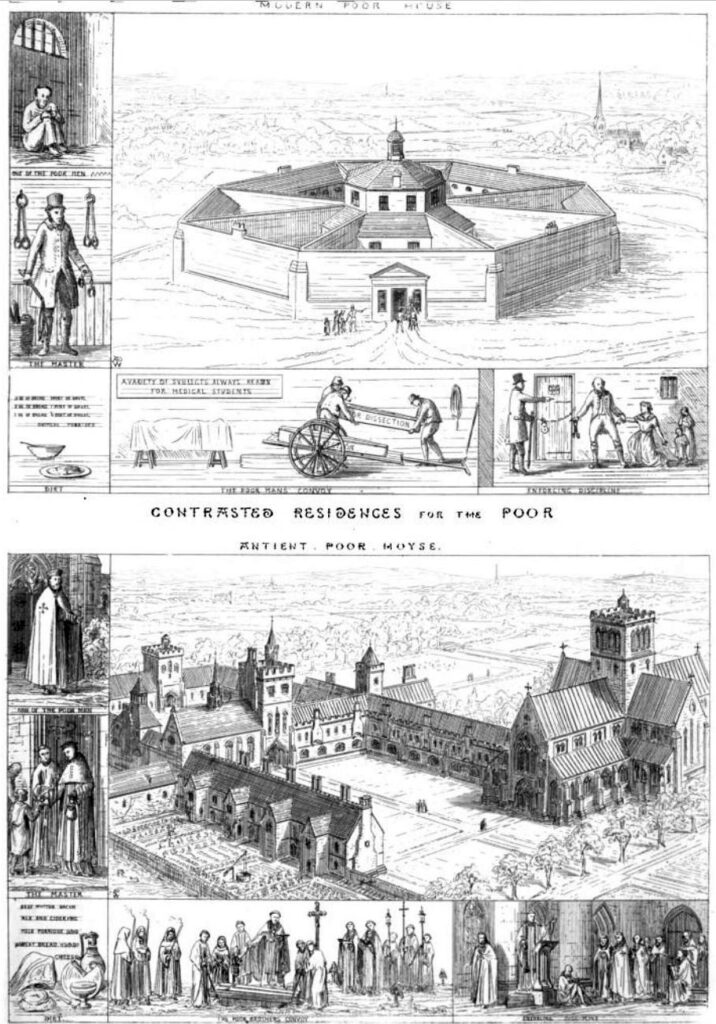

In 1836, Augustus Pugin published ‘Contrasts,’ a book that was comprised of borderline libelous drawings posing the perfect Medieval world against the supposedly dreadful industrial one. Never mind that it was comedically disingenuous – if the means justify the ends, then Contrasts was one of the best books of the century, for it was instrumental in the Gothic Revival and the ensuing phase of some of the finest architecture and urban planning we have ever seen.

The principles instituted by Pugin lasted until the Art Deco revolution of the 1920s when, suddenly, streamlining and simplicity became the rage.

Art Deco is, in and of itself, fine. I’m not its largest fan, but I can certainly admire a lot of its products – posters were where it excelled.

The trouble is what Art Deco represented, and led to. An Art Deco building’s visual interest is near-entirely created by the architect, not the craftsmen who actually construct it, and this appears to have inflated the egos of mid 20th Century architects to the point where they eventually, and summarily, decided that only they were permitted any artistic expression.

Its insistence on clean lines and uniformity paved the way for modernism, in which the craftsman is robbed of much of their creativity. No room for carvings, ornamentation or fractals of detail that impress at every level: the building is one person’s grand plan, a temple to their conceit, and nothing can obstruct their genius.

By contrast, a well-built ‘traditional’ (pre-Art Deco) structure is like a play. The architect may be writer and director, but the actors are the masons, bricklayers and carpenters, who are each granted their own individuality and flair.

An extreme example, but I once had the privilege of spending some time with the resident masons of Hereford Cathedral, one of the few remaining teams in the country who still work on site shaping new stones for the building’s maintenance. They are highly skilled, highly respected individuals who use their creative expertise to choose and create designs themselves – for example, gargoyles and grotesques are regularly replaced, and the masons often carve humorous references to the news of the day (it’s quite fun to try and identify them!).

Who the masons are matters – not necessarily because of their talent, but because of their suitability as actors for the role, just like in a play.

In a typical construction today, however, the role of personal expression for the craftspeople is much more limited. Can a modern builder slip references to the news, or an appreciation of nature, into their work? No, they have to follow relatively exacting plans.

This is something that people often miss when they bemoan the loss of historic architecture. The real ‘problem’, insofar as there is one, is not that architects need to design better looking buildings (though they do), it is that architects need to take a step back, and leave more of the construction process to competent tradespeople.

Of course, this is much easier said than done. Competent tradespeople don’t just appear out of thin air, and there are obvious cost constraints that can demand simpler construction techniques. But just because something is not possible in every circumstance does not mean it should not be done in any.

Fortunately, there does already seem to be a social shift in favour of apprenticeships and trade-based education. But we need to shift our attitudes towards construction itself to keep up. If we are going to genuinely respect the trades, then we need to genuinely respect tradespeople, and permit them to once again fashion our world. Even if it is only in the most expensive buildings at first, we will be leaving a legacy that will be thanked a thousand times over.

Leave a comment